"The perfection of hunting spelled the end of hunting as a way of life....The hunters at the end of the Old Stone Age...broke rule number one for any prudent parasite: Don't kill off your host. As they drove species after species to extinction, they walked into the first progress trap."

—Ronald Wright in A Short History of Progress, pp.39-40.

2.6 MILLION YEARS AGO

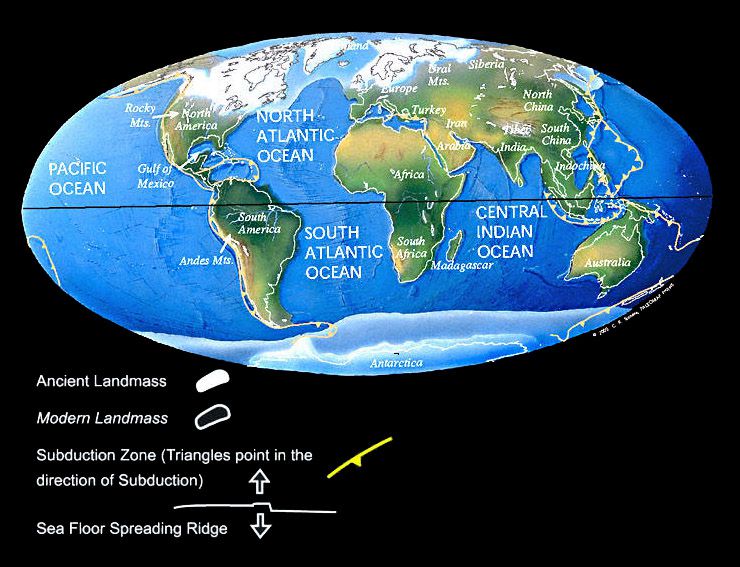

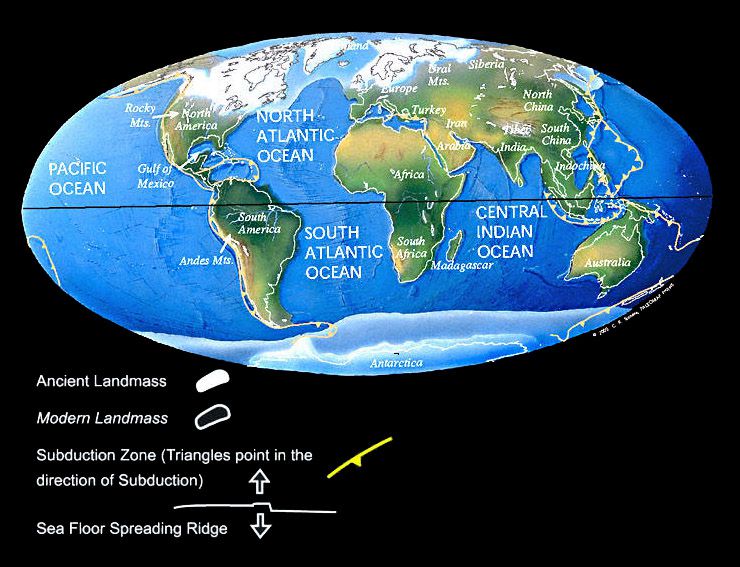

Fluctuations in worldwide temperatures marked the beginning of a series of glacier and ice sheet advancements called Ice Ages, followed by periods of warmth where the glaciers and ice sheets retreated called Interglacial Periods (1). A typical glacial and interglacial period may persist for thousands of years, whereas the move between Ice Age to interglacial period and vice versa can be gradual taking up to a couple of centuries or longer but can reach a point when temperatures suddenly jump (usually within a few years, which is extremely quick in geological terms) as if a switch had been turned on (or off) and the temperature stays in the new position for a long time.

Towards the end of an Ice Age, there can be several moments when an unusually warmer summer can cause massive ice sheets to break off and form an armada of icebergs to float and affect ocean currents. As the icebergs melt, the colder fresh water can stop warmer ocean currents from flowing to certain continents resulting in a sudden and more severe Ice Age over those continents. A classic example are the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea flowing to the North Atlantic and providing warm and wet conditions to Europe. Stop this warm ocean current flow and the risk of a severe cold snap or to maintain an Ice Age in Europe is greater. But in the summer, the temperatures can swing dramatically in the opposite direction to repeat the process.If enough ice melts and the ocean temperature rises sufficiently in the summer months, a point comes when the "switch" turns on. Then the warm currents can flow and a burst of methane from underneath the oceans can emerge to warm the atmosphere and put an end to the Ice Age.

Towards the end of an interglacial period, the higher sea levels and sufficient time sees much of the methane in the atmosphere get re-absorbed, pushed down deeper, and under pressure and lower temperatures, get trapped inside the icy cages formed by the water molecules. Take out enough methane together with enough carbon dioxide absorbed by healthy and vast plant population, and world temperatures drop. Then a different "switch" is turned on suddenly, which sees a long period of intense cold from the polar regions get blasted across large swathes of the Earth's surface. Lands freeze up more quickly than over the oceans. This is the start of an Ice Age.

During the last 2.6 million years since the present time, glaciers and ice sheets have advanced at least five times — the last of which occurred between 80,000 and 11,000 years ago. During the last Ice Age, sheets of ice up to 2 miles thick unfolded over Canada and northern parts of the United States, Europe and Russia. Summer temperatures in Europe and Russia during an Ice Age can be as low as -19°C at night in the winter and perhaps not much higher than 10°C during the day (in places like Germany and other areas with a similar geographic latitude along the European and Russian continent). That's the good news. Needless to say, the conditions in winter were much more colder and severe, especially in Europe.

In most parts of the world, Ice Ages forced a number of animals to migrate to the tropics for greater warmth leaving behind a few hardy species adapted to the cold, such as Woolly Mammoths and humans.

The only few places where other animals could stay put because of the abundance of food and warmth would be in the tropics and, surprisingly enough, the southern parts of the United States. In fact, in the latter case, scientists have discovered that the ice sheets covering Canada and the northern parts of the United States acted like a huge mountain range, forcing warm and moist air travelling from the tropical equator to the north Pacific ocean to be pushed south and get raised over the Rocky Mountains and ice sheets to create extra rain. Thus in many places such as California and beyond the Grand Canyon, one would be able to observe huge forests carpeting down the mountains and opening up to grassy pastures. A number of valleys would also have rivers and swamps with numerous trees lining the shores of the fresh water supplies. A far cry from today's deserts we see in the south-west corner of the United States. Evidence for these moist and warm conditions in the southern United States can be seen in fossils of large mammals and well-preserved dung left behind inside caves showing the type of plants that grew on the continent during the ice ages.

Because of the sheer amount of water that was locked up as ice on land, ocean levels were lower than today. For example, during the last ice age, sea levels dropped by at least 180 metres. So in places like North America, herbivores could enjoy up to 35 kilometres of extra grassland extending to the sea.

In Europe and Russia, native animals were not quite enjoying the same balmy conditions in the same way as their American counterparts. Here the summers were much shorter, and the winters long and brutal in terms of a much lower temperature compared to the United States. Any animal living in Europe and Russia had to quickly decide how to survive the long and cold winters until the very short springs and not much longer summers came around. This meant that for animals living on the surface, virtually all had to evolve thick fur as a natural biological response to the intense cold. The next problem is where to find food. There are essentially two methods for herbivores: either quickly consume and store food inside underground burrows where the animals would hibernate, or migrate to where fresh grasses can be found (i.e., regularly move according to the seasons). For the hibernating animals, the biggest problem was building or finding an underground home located low enough below the surface not to cause the animals to freeze during winter and at the same time hope the entrance way will not be completely covered by ice to stop the oxygen from getting to the animals until the next spring season commences. For other animals, including the large mega-faunas such as Wolly Mammoths, bisons, reindeer and other herbivores that couldn't dig burrows or find enough large caves to shelter from the cold, migration was the only essential means of survival. By migrating, the animals could move sufficiently south to get away from the ice sheets and into vast plains of mostly treeless pastures containing a rich supply of different varieties of grasses and low lying flowering plant species.

Unfortunately for these migratory animals, another species would also do the same: early humans.

In the coldest period of the last Ice Age, roughly 24,000 years ago, the European ice sheets extended over England, Germany, France, Poland, Switzerland and some other countries, and probably encroached into parts of Spain and Italy. In Spain, the ice sheets may have extended down from the western side of the country and entered into what is now Morocco in northern Africa. About the only place considered bearable for animals to live were along the shores of a large inland body of fresh water in a deep valley (which would later be filled by the Atlantic ocean to form the Mediterranean Sea soon after the end of the last Ice Age).

Where water separates Russia and Canada today, the ice ages saw the two land masses joined together as one. This may suggest a free flow of animals going back and forth across the land bridge between the two continents. However, the reality is that at the height of these ice ages, great ice sheets would have effectively stopped the migration of large mega-fauna between Russia and the United States. Perhaps the only exception to this is during the small climate window of opportunity at the beginning of the interglacial periods where just enough ice would melt to provide the necessary open corridors of grassland for the more curious animals to try their luck at finding a new home (and before the oceans rise up high enough to stop this migratory path). But leave it too late and the Arctic and Pacific oceans would naturally rise to provide their own form of a physical barrier to the animal migration. Only humans would be smart enough to have learned of ways to build small boats to navigate the waters but always keeping close to the shores.

During the beginning of the first glacial advancement nearly 2.6 million years ago, many extinctions occurred suggesting a number of animals were caught off-guard (or chose not to adapt to the new conditions) by the sudden drop in temperatures. Fortunately for us the road to our evolutionary existence continued, suggesting we learned to adapt or move to new locations.

NOTE: It has been hotly debated by scientists as to whether these glacial and interglacial periods were caused by variations in the distance between the Earth and the Sun over time, and the presence of volcanoes. For example, should the Earth move slightly further away from the Sun, world temperatures can drop. On the other hand, if volcanoes erupt, extra carbon dioxide can help to raise world temperatures (especially if methane ice melts sufficiently to become an effective heat trap in the atmosphere). However, the kind of oscillatory behaviour in world climate we see after 2.6 million years ago is suggesting a fine balancing act was taking place between plants and animals in the way they affect the chemistry of the air and with it world temperatures. We know Earth was a more geologically stable place at this time with far fewer volcanoes. The Earth's orbit was also relatively stable too. This leaves us with the one big variable in all of this: the population levels of certain lifeforms and the sorts of gases they can absorb and emit to affect world climate. More specifically, animals and plants can affect the ratio of carbon dioxide / methane and oxygen in the air. Sure, volcanoes. asteroid impacts, and even the seemingly insignificant actions of emitting dust and soot into the atmosphere from man-made fires can affect world temperatures, but the Earth and the living things present on its surface has a way of balancing the effects of climate change. Of course, today things are different in the sense that humans are having a substantial impact on world climate without realising it. If humans had no impact on the environment and plants were in abundance as we speak, then things would have cooled down by now. Give it a bit more time and Earth would experience another Ice Age. However, our technology and activity since the 19th century has stopped this natural oscillations in world temperatures. Our dominance on this planet seems unchallenged if not at our own peril should we not heed the warning signs. Because so far there is less and less of the healthy plants in tropical regions to help balance the rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. Soon methane gas will leak out of the permafrosts and deep in the oceans to raise world temperatures. Then the burst in an unexpected amount of methane will see temperatures rise dramatically. And with many short-term thinking humans still desiring profit above long-term survival by selling natural plant resources as well as minerals underground to other humans who need or want to buy it without sufficient replenishing of plant stocks and preserving the native animals that plant life depend for reproduction and the supply of natural fertilisers and very soon we will all face a great disaster. Will our brains be big enough to realise what we are doing?

2 MILLION YEARS AGO

A particularly warm period prevailed at this time for some reason (presumably because humans where releasing more carbon dioxide from burning wood, with less of a contribution from increased volcanic activity). Anywhere between 3 to 5 degrees higher than present-day temperatures saw a reasonable amount of ice melt and sea levels rose by around 20 metres.

1.5 MILLION YEARS AGO

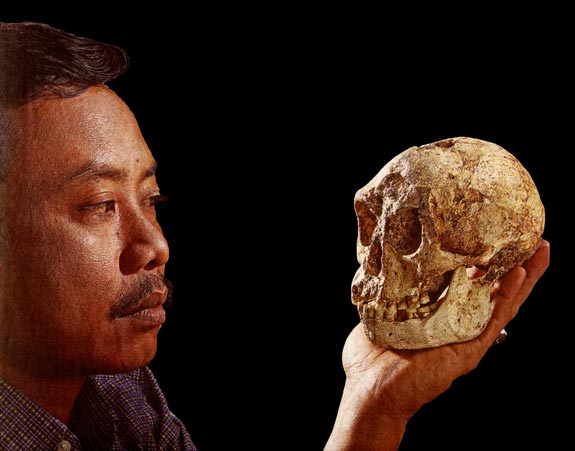

Early humans have now evolved (or appeared side-by-side with Homo Augasta) to the level of Homo Erectus. The name is rather unfortunate for it conjures up images of sexually promiscuous male hominids marauding the countryside. Although there may be some truth to this, the term Homo Erectus was devised to highlight the fact that these creatures walked upright! Does this mean these creatures were the first to walk upright? No. Earliest evidence of upright-walking hominids have now been dated back to as early as 6 million years ago after the discovery of more fossils. The name Homo Erectus has been kept for posterity sake as it reminds people that fossils of this hominid were the first to be discovered by scientists to show this clear and unmistakable upright walking feature.

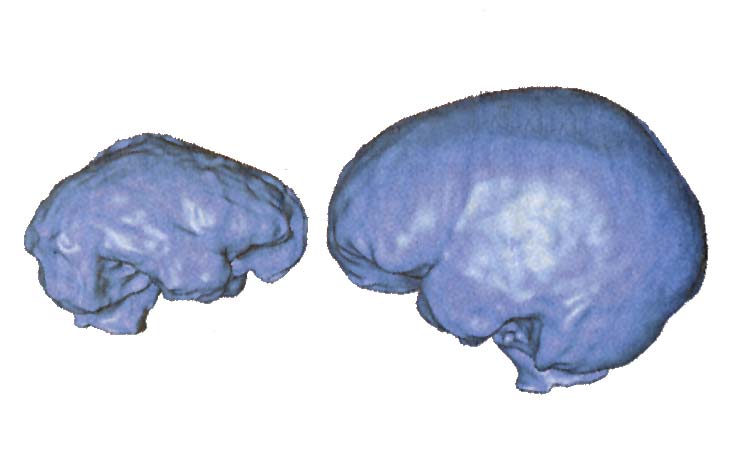

At any rate, we see these upright-walking creatures have developed a larger brain than their predecessors (but still smaller than those of modern humans). A noticeable jutting ledge of bones over their eye sockets still apparent. On the other hand, they had smaller canine teeth, and their jaws were receding suggesting mastication of foods was easier. Does this mean these hominids had mastered the art of building fires and cooking their food (probably mostly meat scavenged from dead animals)? Most likely. Indeed, some scientists are willing to bet that the earliest time when fire was created by ancient hominids was probably around 1.8 million years, quite possibly in response to the colder ice age conditions and the need for hominids to be inventive in finding ways to keep warm. Cooking of food probably became a secondary benefit as these hominids looked at the power of fire to do more in their lives.

Homo Erectus was known to inhabit caves for its protection and warmth, especially during the glacial periods.

Is Homo Erectus a direct link to modern humans? Most probably on the grounds that its facial features looked more human than any previous hominid. As Professor Travis Pickering at the University of Wisconsin said:

"It's the first early human that has really modern human characteristics, really big brain and indications that it was a big game hunter."

But then again other independently evolved (or perhaps separate species that branched from an earlier common ancestor for all hominids including us) did exist in different locations. Could the humans traits we have today had been acquired from a number of different species? Or did one species "go at it alone" and competed successfully to become the dominant hominid of all other hominids, and Homo Erectus is really the product of that very species that would lead to the modern human lineage we see today? We can only speculate at the present time.

Whether we descended from Homo Erectus, it is believed this particular hominid species did migrate to Asia between 1.7 and 1.5 million years ago. One theory for the migration is because, during interglacial periods (for which there had been quite a few since 2.6 million years ago) when the planet warmed up, geological corridors of greener pastures allowed some groups to move out of Africa and away from the intense competition for food by other hominids. Another theory is that a group of Homo Erectus individuals developed a gene mutation that resulted in more whiter skin. The mutants then had to migrate from the continent to preserve their differences from the darker-skin African groups that may have thought the mutants were odd-looking and possibly inferior (funny that considering in recent times we see it is the white-skinned humans who are looking on the dark-skinned people in a similar way).

1.1 MILLION YEARS AGO

The general consensus among scientists is that truly modern humans probably emerged from Africa at approximately 200,000 years ago to explore and populate the world. This view is known as the Eve theory in memory of the classic Western religious story of Adam and Eve. On the other hand, Asian scientists, notably the Chinese, argue their fossils of early humans existed well over 300,000 years earlier and as old as 1.1 million years ago as if other hominids had already existed and may have evolved independently into Homo Sapiens. One supporter of this "we already existed in Asia" theory is paleontologist Wu Xinzhi. Interestingly the findings of some skulls in Asia dating back to this time do appear to suggest hominids in Asia were probably evolving more quickly to have features reminiscent of Homo Sapiens. But at the same time other more recent finds are suggesting there could also be new species of hominids or species from an older genus that arrived into Asia that lived independently and which had not evolved significantly due to the limited competition and more isolated nature of the forests that existed in China during the ice ages and into much of the interglacial periods.

Were there a single region in the world for the origin of all modern humans? Or were there several cradles for modern mankind within Europe and Asia and not just Africa?

Considerable debate still remains as to who exactly existed where and when and whether early hominids had already populated much of the world at this time to evolve independently into modern humans. But if we are to accept latest DNA analysis of modern humans and tracing back the genes to the common ancestor, it is clear at least one hominid with a direct link to modern humans had definitely come from Africa, and they were moving into new territory including China. Thereafter it becomes a question of how these migrating hominids filled the presumably empty void of other continents to populate them with their own kind, or whether there was some intermingling with existing hominids.

It remains a difficult question to answer until more bones from China are uncovered and analysed.

Maybe we had a situation where the slightly darker-skinned (but whiter than most other African hominids) and larger-brained Africans living on the coast and feeding on mussels saw the attractiveness of whiter skinned hominids in Asia and elsewhere and from this came a hybrid human with a larger brain and white skin to become the first true modern Asian people? Although something is telling us, this is unlikely. Given how different the appearance of other species in China have been noted when we analyse the more recent and unusual skull remains from China (including cheekbones, jaw structure, and brain capacity) and realising these features are much older and less attractive, it would suggest that the more prettier and larger-brained African species with a more modern-looking face had probably kept to within its own species. And if there is any competition or violent tendencies by these more primitive hominids toward the larger-brained newcomers from Africa, it is likely these older species would have quickly been pushed out of the territory and ultimately become extinct if they were not intelligent enough to find new locations far enough away from the competition or figured out ways to fight back. It would be a situation of what we have seen for the Neanderthals in Europe as Homo Sapiens entered their territory and were cutting down trees, making it harder for the Neanderthals to creep up on prey using trees to hide and pounce on the animals and eventually the Neanderthals were too weak, died and became extinct. Of course, more work needs to be done in this field to determine the real truth for hominids in China.

UPDATE

June 2014

Recent excavations of some interesting Chinese hominid remains including skull fragments from a cave near the village of Longlin in the Guangxi Zhuang region and from Maludong (known as the Red Deer Cave) in the southern Yunnan Province show evidence of a primitive hominid species, but with some modern features. On closer examination of the skull structure, the primitiveness of the hominid can be observed from the bottom of the nose upwards, together with an unusually wide set of cheekbones. However, below the nose, the hominid possessed a large and unusually modern human-looking jaw structure. In fact, some scientists have thought of the possibility of hybrid breeding with modern humans who came into the area nearly 50,000 years ago and a more primitive hominid species that already lived in China to account for the remarkably modern human jaw structure. However, the primitive aspects mentioned for these so-called "hybrid" Chinese human remains have been observed in some African hominid species as far back as 1.6 million years ago when the first Homo Erectus creatures migrated to Asia, and certainly in much earlier times from a number of other hominid species that existed in Africa (including the Australopithecines). For example, one species from the African continent having a wide set of cheekbones at around 1.6 million years ago is Australopithecus boisei. But it is likely other species, including some types of Homo Erectus creatures, had already carried this physical attribute and may have migrated to Asia to preserve this specific physical characteristic. Indeed, by the time Homo Erectus did arrive in Asia (including China) around 1.6 million years ago, it is known that a number of Chinese Homo Erectus skull remains have been unearthed showing a more flat face with "prominent cheekbones". If this is true, a highly isolated group of this species may have evolved independently in China to develop a more wider cheekbone structure but retained much of the primitive Homo Erectus upper skull features (since problem-solving was not considered by these hominids as a necessary requirement in this food plentiful forest region of China together with less competition from other hominids). The only thing that may have evolved more significantly would be the jaw structure to match the type of diet these people chose to have in this region. Thus, it is likely the species found here, named Homo Mituan (or Enigma Man), despite the unusual appearance and surviving up until 11,400 years ago due to their isolation in China where they lived, is just such the remains of Homo Erectus surviving far longer than would have been expected (despite some scientists thinking this species should have disappeared 500,000 years ago). Of course, the only way to confirm this situation is through DNA extraction and analysis, except the DNA quality of the bone is too poor to gather any meaningful information at the present time.

The people working on the Homo Mituanis species in China as of 2014 are Professor Ji Xueping from the Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, and Associate Professor Darren Curnoe specialising in palaeoanthropology at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Further details of the study can be found in the 14 March 2014 edition of the journal PLoS ONE. The article is titled "Human Remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition of Southwest China Suggest a Complex Evolutionary History for East Asians".

NOTE: The ability of more primitive hominid species to survive longer than expected is not a new discovery. Scientists have noticed how the last remaining Neanderthals of Europe survived up until 24,000 years ago, and Homo Floresiensis (also known as "the Hobbit") from a small Indonesian island surviving up to 17,000 years ago. One of the defining factors as to why these species can survive as long as they did is due to their isolation. However, once modern humans discovered their presence, the more primitive species will often come out second best in the encounter as it seems modern humans are keen to control new territory and food supplies and usually do not take too lightly to extra competition from other species, or simply for the fact that the primitive species do not look "attractive" to modern humans and stories might get made up to make these species look scarier than they really are and eventually the next generation of modern humans may act on the stories thinking they might be true and eventually the primitive species get wiped out completely from the area.

1.05 MILLION to 780,000 YEARS AGO

Scientists believe another reversal of the Earth's magnetic poles occurred during this time when the north pole was over Antarctica again. But this one lasted for around 200,000 years — a mere blink of an eye in geological terms! (2)

Mammals living at this time were not as big as the great dinosaurs of the Jurassic Period or even the giant mammals of nearly 5 million years ago, but were still considered much larger than animals of today. Only the elephants of our times could possibly compete with some of the animals that lived around 1 million years ago such as the giant ground sloth (now extinct). Although it would struggle to compete in size with the Wolly Mammoths in Europe and Columbian Mammoths in North America (a less hairy creature compared to the European species).

It was also the time when the sabre-toothed cats with their pair of 7 inch fangs clawed its way onto the world stage as the most dangerous known non-human predator. Weighing as much as 300 kilograms for a fully-grown adult, the sabre-toothed cat was a formidable opponent. So fierce was this animal that it would eventually see the demise of the flightless terror birds. However, the sabre-toothed cats would have a couple of disadvantages: the two long teeth emerging from the mouth were only useful to eat the fleshier parts of a prey leaving behind a lot of wasted meat and bone. Also these predators were short range runners despite their explosive power of acceleration. The amount of energy required to chase prey would see the sabre-toothed cats catching large prey every few days just to recuperate their energy before preparing for the next kill.

Then the climate got colder and drier. Less vegetation on the ground would see many of the larger herbivores become extinct due to limited food, leaving behind a number of smaller animals to thrive in the harsher environment. Only a few large herbivores with the right tools (e.g. fur and a long tusk to scrap snow off the grass) would have a better chance of surviving the colder conditions. Of special mention in this regard are the wolly mammoths.

As temperatures went down for the next ice age, sabre-toothed cats suffered greatly under the conditions by not finding enough food (and perhaps with another force to contend with — humans). In fact, the colder things got, the less plant food available, and the smaller the plant-eating animals have to be to survive on the remaining food supply. But as soon as the big plant eaters died, the big predators soon become extinct.

Assuming human did not contribute in some negative way, we must assume this is how the sabre-toothed cats eventually became extinct.

NOTE: The largest Australian marsupial flesh-eating lion known to scientists as tharlac oleo lived in the tree-filled Nullabor region of Australia at this time. This is a lion rising to half the height of a human while standing on four legs. A stabbing incisor at the front of the jaw and powerful claws gave this ferocious creature the power to hold prey and puncture terrible holes in the skull or cut the spinal cord and back teeth capable of shearing off huge chunks of flesh. It can balance itself on two legs on its long tail and stand taller than a human. The animal could climb trees and jump down on its prey. This is a big, robust muscular predator. It survived until the first humans arrived in Australia.

1 MILLION to 800,000 YEARS AGO

Latest research in 2010 suggests the oldest known fires used for cooking food have been dated to around this time although there is every indication cooking may have taken place as early as 1.6 million years ago based on analysis of the teeth of Homo Erectus.

Some scientists believe cooking became the next important milestone in the history of humankind because with cooking came the opportunity to release a greater amount of energy by way of carbohydrates in plant foods and to make digestion of proteins from meat into relevant amino acids needed by the body much easier and quicker. It meant early humans with their smaller and sharper teeth and lighter jaw structure did not have to masticulate on raw plant foods for long periods of time and then have to sit around in the safety of trees for many hours to conserve energy in order to allow the digestion process to complete as it had often been the case for the Australopithecines. There is also another greater benefit cooking brought to the early humans: the brain could rely on more energy in the food to power the evolving functions needed for longer concentration and other problem-solving abilities. So long as early humans used their extra time to think about how to do things better, which clearly they did at some point when they made their own fire and started cooking food, then there is no reason why the brain would not have evolved more sophisticated higher functions to permit more effective problem-solving skills.

Among the supporters of this theory is Professor Richard Wrangham of Harvard University. As he remarked:

"Do you know what chimpanzees spend most of their time doing? They spend most of their time just chewing. And Australapithecus would undoubtedly have done the same thing. Probably more than half the day, they would have spent their time just moving their jaw up and down because they are eating a relatively low quality food compared to us. They spend most of their time doing nothing other than eating.

The Australopithecene brain size remained stable. Then meat eating came in, and then the brains got bigger. And that set everything off in the direction of modern humans."

Thus when cooking become integral to the meat eating diet of early humans, the quality of the food's nutritional value must have dramatically increased. As Professor Wrangham believes:

"Cooking is huge. I think it's arguable the biggest increase in the quality of the diet in the whole of the history of life."

Of course, what would happen if early humans discovered how cooking soya beans would provide all the protein and energy? Would it be necessary to continue eating meat in order to develop a bigger brain? Probably not. However, humans in Africa were experiencing lower rainfalls and plant life was diminishing, making it less likely these hominids would have discovered this possibility and started cultivating the lands to grow protein-rich plant-based foods such as soya beans. In fact, there is no evidence as far as we can tell that soya beans ever grew in Africa. Perhaps this was something the hominids in Asia would discover at some point in history. However, in Africa, meat was the principal diet for early humans.

With this heavy reliance on meat for its survival came the advantage of developing a bigger brain. s the brain grew, it seems humans were developing good communication within a social group, as well as long-term planning and the ability to visualise or experiment directly in the environment with new tools when finding better solutions.

While all this cooking activities were taking place in Africa by some early humans, on the other side of the world a new island appeared out of the Pacific Ocean. Initially created by an exceptionally hot and highly fluid magma spot below a thin crust, a massive volcano suddenly erupted from the sea floor nearly 1 million years ago. As the Pacific tectonic plate moved, new volcanoes would erupt from time-to-time from the same hot spot forming the eight main islands and a total of 19 volcanoes we know today as Hawaii.

NOTE: Verbal communication is not unique to humans. Even a dog will attempt to communicate with its human master consistently and even closely mimic the sounds of its master even if its voice box cannot create the precise sounds that a human can produce. A dog, for instance, when rewarded with what it needs at the right time when the human master is displaying a consistent and regular verbal communication cue to the dog, it is remarkable after a while to see how the dog is willing to try mimicking those sounds of the master, especially when the dog knows it is time to re-experience something again in association with those sounds. It is, therefore, likely that very early humans must have seen communication in a similar way, through a reward-based system where certain different sounds were created and mimicked by humans when associated with specific experiences or types of objects. And if the sounds can be amplified by the voice to cover reasonable distances, this would have improved the chances of survival for humans immensely (so long as the sounds do not suggest to a predator of a different species that might be seen as food and is surprisingly close by).

700,000 to 500,000 YEARS AGO

With another modest increase in brain capacity in such areas as muscle co-ordination (i.e. the cerebellum and the motor control strip running along the top part of the cerebrum) and ability to concentrate a little more on complex tasks (i.e. an expansion of the frontal lobes), as well as favourable interglacial periods that allowed the great African continent to open up to a whole new world in Europe and the Middle East in the north, Homo Erectus eventually moved to the furthest parts of the world including India, China and Java (and soon to Australia), where they may have learned to intermingle with other similar people or kept to themselves and continued to master the use of fire for warmth, protection and for cooking. (3)

Scientists at the London Institute of Brain Chemistry have recently proposed a new theory for why the brain size has increased. The suggestion has been that early humans were able to develop bigger brains because they chose to eat more fish.

Well, there may be some truth to this since it is now known that fish contains valuable proteins. Perhaps we shouldn't be too surprised by this discovery. However, scientists suggest fish carries another vital ingredient for the development of a bigger brain: Omega 3 DHA. Indeed, the combination of proteins, fats (e.g. Omega 3 DHA) and minerals found in fish would have made this source of food an absolute bonanza for building and powering the human brain. As one anonymous individual remarked, "Fish is the rocket fuel for the brain."

It kind of makes sense this fishy idea considering it is a veritable fact that fishing is still a major part of modern human life in the 21st century and hasn't changed for thousands of years. With nearly 90 percent of the human population choosing to live in or near the oceans or major waterways probably because of the relative ease in obtaining seafood in vast quantities (this may explain how we moved out-of-Africa nearly 160,000 years go to populate the world), it would seem natural to suggest that fish may have played an important role in early human brain development for at least 500,000 and possibly as far back as 5 million years ago.

However, we must be careful not to see fish as the sole agent for building bigger brains. Fish on its own is not enough. Or as they say, "Man cannot live on fish alone" (or was that bread?). To make the brain bigger, humans must learn to use the brain to absorb and process information in order to extract, create and apply new patterns (both visible and invisible) relevant to survival and/or to improve one's social status in a group of other humans. Then, as the brain is used to solve problems and fish is consumed, the combination of both activities would have helped to contribute (together with a little genetic mutation here and there) to a bigger brain.

Let us put it this way, it would be perfectly reasonable to think that humans would have wanted to remember specific patterns related to the recognition of various predators existent at this time. A good reason in itself to use the brain to remember these patterns, or else you will get eaten alive. Then there are plants to remember in terms of their medicinal purposes or as a source of additional food to supplement one's meat-eating diet. The other way, is to develop a communicative language. Beyond that, some humans may have learned about the bigger and more invisible patterns in the universe which help to give a clue about the meaning and purpose of life and the universe, why we die and what happens to us after death. Whatever patterns we are likely to acquire and remember, it seems all this is a question of whether the individual learns to make the choice of using the brain to solve problems and remember a number of essential patterns needed to survive a harsh and difficult environment, and not just eat fish, which determines exactly how large the brain needs to be to handle the situation. Like the old saying goes, "Use it, or lose it." Otherwise, there would be no evolutionary advantage in growing a big brain by eating lots of fish.

So there must have been a moment when humans did apply the human brain more often to problem-solving and to remember things with increasing ease. Well, given that today we can see how much energy has to be used from the human body to power the brain (scientists have estimated 20 per cent of the total energy consumed in modern humans), it seems using the brain must have been important in the past to increase its size and use up lots of energy. How would early humans have used the brain to achieve this?

Given the amount of energy required by the brain, it probably required the body to be at rest for extended periods of time to allow humans to think and solve problems. Seems logical enough considering humans were getting efficient in gathering food and were having more time to rest and think about things. But at the same time, it is a well-known fact of chemistry and in biology that systems would prefer to minimise the amount of energy it needs to achieve a certain result. That in itself is a good enough reason why evolution would not favour a large brain irrespective of how much fish we eat unless there is something else making us use the brain to make it bigger. To make the brain bigger, humans must have had more free time to sit around and figure out what to do next and start planning ahead on what to do and how to prepare for various events. Then some of the males may have learned and passed on to future generations what's important to remember and which actions should be practised of greatest benefit to survival. Females would eventually have their own time to think about things, usually relating to how to look pretty, discussing relationships and doing other things. By sitting around, the body would have the energy and time to power the brain and not feel burdened by this mental activity performed over long periods of time.

We call this a natural application of our brain to acquiring and creating new patterns in a process known as learning.

Depending on how we learned to survive, humans either used their bodies or brains, or a combination of the two to solve problems. The easiest would be to rest the body and apply the brain, and later apply actions with the body, especially when free time became available. But if not, brute force might be the only answer.

At any rate, once free time was available and there was adequate food to build the brain, the application of the brain on a regular basis can only make it bigger and/or better organised to allow future generations to find it easier to apply problem-solving skills to a given situation in a more efficient and effective way.

As the brain was being applied on a more regular basis to problem solving and remembering essential patterns of behaviour of animals and among fellow hominids as well as developing an expanded but still relatively rudimentary form of communication, we also see emerging from the Homo Erectus lineage two interesting hominid groups. One group would migrate and rely more on the body and brute force to find solutions to surviving the great cold of Europe known as Neanderthal Man. The other group would live in Africa relying increasingly more on the brain to survive by sifting out important patterns in the environment for survival and how to chase their prey over long distances or choose a different diet of seafood (e.g., mussels and oysters) to help reduce the amount of running around while developing a more sophisticated language for communicating with fellow hominids and females would have more time to make themselves look prettier.

No doubt the latter group would lead to modern humans.

500,000 YEARS AGO

The world's oldest DNA was uncovered in 2007 under a kilometre of ice in southern Greenland showing much of the land was truly green during the summer as the name implies. There existed a temperate forest consisting of spruce, alder, pine and yew before ice permanently covered all of Greenland. Joining the lushes forest was a healthy quantity of butterflies, moths and the ancestors of beetles, flies and spiders, just to name a few species.

As researcher Professor Eske Willerslev said:

"We have shown for the first time that southern Greenland, which is currently hidden under more than two kilometres of ice, was once very different to the Greenland [of] today.

Back then it was inhabited by a diverse array of conifer trees and insects." (Smith, Deborah. Greenland really was green, world's oldest DNA reveals: The Sydney Morning Herald. 7-8 July 2007, p.7. & Jha, Alok. Greenland really was green once: The Canberra Times. 7 July 2007, p.19.)

The DNA to support these plants and animals was uncovered from cores drilled into the ice cap and into the muddy bottom. Through careful analysis of this material, the DNA of the ancient insect variety has been estimated to be between 450,000 and 800,000 years old.

Australian researcher Michael Bunce, who joined the Danish-led team to help extract and analyse the ancient DNA, said:

"Preserved DNA from plants, animals, insects and bacteria that died hundreds of thousands of years ago can aid in our understanding of how the earth's environment has changed." (Smith, Deborah. Greenland really was green, world's oldest DNA reveals: The Sydney Morning Herald. 7-8 July 2007, p.7.)

For example, Bunce has now realised how the ice did not melt during the last interglacial period of 116,000 to 130,000 years ago when temperatures were believed to be 5 degrees higher than today. For if it did, the ancient trees and insects would have been replaced by new varieties of flora and fauna. Instead, life of half a million years ago was preserved in Greenland's giant natural freezer.

The implications of this simple yet important discovery is that it may take longer for the ice sheets in Greenland to melt under present-day global warming conditions. So does this mean there will be no sea level rises today? Not necessarily so. The last interglacial period may not have seen ice on Greenland melt, but somehow the ocean levels did rise by 5 to 6 metres higher than today. Clearly this rise had to come from other sources, possibly from Antarctica. More research is taking place to figure out precisely where the melted ice was coming from.

As Willerslev stated:

"As the Earth warms from man-made climate change, these sources would still contribute to a rise in sea levels." (Smith, Deborah. Greenland really was green, world's oldest DNA reveals: The Sydney Morning Herald. 7-8 July 2007, p.7.)

Scientists have estimated that Greenland of 500,000 years ago had a summer temperature of 10°C, and -17°C in the winter.

More details can be found in the journal Science published on 6 July 2007.

NOTE: Where there is ice over the oceans, the melting will occur more quickly than on land. Oceans have a greater capacity to hold more heat compared to land masses.

400,000 YEARS AGO

Rapid changes in climate every 400,000 years when the Earth experiences the most elliptical orbits and other factors seem to force the brain of humans to expand. How? By getting humans to regularly problem-solve — the most common of which involves finding food. But during these very long cycles, humans also had to deal with climate change. Thus the more regular problem-solving efforts humans perform such as where to go, choosing different foods, improving hunting techniques, and learning to socialise and getting people to perform important and needy tasks for the group can not only increase the size of the brain but could also be the result of environmental conditions caused by changes to the Earth's axis of tilt and how the planet moves around the Sun. Regular problem solving of this kind during periods of sudden climate change has probably helped over many generations to transfer the necessary genetic changes needed to build a larger and more powerful brain. In essence, the more problem-solving you do in life, the bigger your brain gets.

300,000 YEARS AGO

Northern and southern polar ice caps expand towards the temperate zones during this Ice Age period. Places such as the Sahara in Africa receive more rainfall to allow trees and other plants to slowly edge their way further north. In fact, the presence of trees in the Sahara would oscillate depending on whether the Ice Age appeared or not. As Sahara gets wetter, regions in which we call Mesopotamia and Turkey would receive more natural greenery and extra freshwater supplies.

The same is true of Australia so long as enough trees grow and help to reduce water evaporation.

400,000 to 200,000 YEARS AGO

Perhaps with all that intermingling with other previously isolated groups, a new species called Homo Sapiens evolved from Homo Erectus (or Homo Augasta) around 400,000 years ago until mostly these hominids walked around some 200,000 years ago. These new hominids had an expanded skull to accommodate a larger-volumed brain, and the entire skull structure became lighter and delicate. No longer are thick brow ridges visible.

The jaw structure of Homo Sapiens reduced noticeably in size and appeared less protruding, resulting in a smaller more modern human face. It is as if the foods they consumed were softer (e.g. more fruits and berries) or were prepared in such a way as to make mastication easier (i.e. they had used fire as a means of cooking their food).

NOTE: Some scientists have placed the origins of Home Sapiens at around 160,000 years ago during a time when significant changes had allegedly taken place within the brain after studying the skull structures dated to around this time.

200,000 TO 195,000 YEARS AGO

After studying the fossil skulls of our ancestors, many scientists believe the larynx or voice box was at one time positioned much higher up in the throat. As with the apes, this higher position prevented speech from taking place. So the most these apes and our early ancestors could do is grunt (possibly whistle) and point a finger or two to help communicate. However, by 200,000 years ago, biological evolution (i.e. the physical changes to the body over time through mutations and regular application of the body for specific tasks) led to a lowering of the voice box, increasing the frequency range in the sound and producing a range of new and different sound patterns. The advantage is clear. If humans could not communicate with their fingers at long range distances (even waving the arms can have its limitations or in showing the fabled one or two finger salute to the enemy), humans quickly learned to use the voice box to send specific sounds over greater distances to communicate a range of different and more richer information about the environment to other humans (so long as everyone understood what the sounds meant).

As with such changes leading up to the generation of more complex sounds and ultimately a language for describing just about everything in the known world, this essentially means a bigger brain for remembering the sounds and associated symbols. Thus it is possible a larger and more complex brain may have appeared for the earliest ancestors of modern humans at around the time the voice box had changed. Certainly greater evidence to support these brain changes would come for skulls dated to 160,000 years ago.

All these changes would also coincide with results obtained through mitochondrial DNA analysis showing the DNA of every modern human race emanated from a single female that lived in central Africa around 195,000 years ago. This remarkable feat was achieved by analysing the DNA inside numerous energy producing structures for powering every living cell called a mitochondria and compared this mitochondrial DNA to the diverse human races found in different parts of the world today. It is in the African people where scientists have managed to trace back the majority of gene sequences of every race on the planet and this gave scientists the first clue to the origin of modern humans. The second clue would come after estimating the time it takes for such genetic changes to take place, which put modern humans as originating in Africa around 195,000 years ago.

160,000 YEARS AGO

The brain structure of early humans (i.e. our direct ancestors) had definitely advanced at this time to a noticeably complex and enlarged level approaching very closely to modern humans of today. As French paleontologist Anne Dambricourt Malassé stated:

"The brain grew much more complex. It had a better blood supply. So, naturally, after this biological evolution a cultural evolution came very quickly. Homo Sapiens was born" (Homo Futurus, a documentary film by Thomas Johnson and produced by Hind Saih in 2005, televised on SBS 6 May 2007)

Those observed changes to the brain from skulls dated to this time are primarily in the region where abstract thinking (as needed to solve problems) takes place, which is the frontal cortex. This is combined with a larger corpus callosum to help shuttle information back and forth between the cerebral hemispheres as needed to break information into manageable and well-understood patterns and reassemble to form the whole image to help the brain quickly recognise known and important large-scale patterns (such as predators, a source of food, or the potential for a new mate) or to creatively come up with new patterns that could potentially solve existing problems in a different and more permanent way. Thus, the skill of thinking (including visualisation as well as immediate recognition of essential patterns) mainly for the purposes of solving problems became more effective and be sustained without too much difficulty. When compared to skulls of other hominid species, this abstract thinking is definitely not as extensive as humans of today. Instead the environmental conditions and choices made by hominids at this time on what is important to survive seem to determine which areas of the brain and the type of senses would be prized and developed further. For example, we see the occipital lobes for processing visual information tends to be more developed and enhanced in a group of hominids called the Neanderthals compared to humans. Visual information is still very important to human life, but it seems humans were learning to apply abstract thinking to solving problems far more than other species. As a consequence, humans would develop dramatically improved memory (both short-term and long-term recall) and thinking, and better visualisation skills (with increased creativity achieved more easily by taking hallucinatory drugs from plants, or else train the mind to maintain a certain level of concentration and visualisation for longer). In the end, such improvements in the brain helped humans to acquire a wider range of patterns to remember, recall, and exploit.

Since the brain became more than just a powerful pattern-recognition and storage tool (as required to recall familiar patterns observed with the eyes, ears and so on) as well as a powerful pattern-creation tool (as required to create new ideas and ways of doing things), the extra visualisation and creativity skills provided by the right side of the brain were helping early humans to indirectly observe more abstract and hidden patterns from the environment and simplify them for easier memory and recall. Before this time, the use of the L-brain for recognising just about every known patterns stored in memory with what was directly observed through the eyes was considered the most sought after skill because this was the way to recognise prey during hunting and to know which predators to avoid. The only problem with this approach is that humans had to take each day as it comes, hoping the food they need to hunt would be available when humans got hungry. Now humans simplified the food gathering and hunting process and began to realise there existed large-scale hidden patterns in the environment showing such things as the timing for when food was likely to be abundant and in which location. This is especially true among those humans who lived along the shorelines. As soon as humans discovered mussels (a valuable source of omega-3 fatty acids needed to build a healthy brain) growing along the southern and eastern African shores, it made sense for humans to stop chasing prey via the persistence hunting method and instead they could plan ahead and time the moment when to walk down to the shores to collect mussels when the tides are low.

This meant learning the pattern of the ocean tides.

Early humans were getting cleverer (and probably lazier too, but then again how do we grow a bigger brain and/or re-organise it to be more efficient and effective at doing things to help us solve problems if we don't at various times rest the body and think about something?). In fact, they were getting so good at this, possibly allowing the leaders to not only plan ahead but also to delegate specific tasks of gathering food at the right times by selected members of the group, that they were learning to find ways to relax and creatively think about things.

Or it could simply be the fact that humans were having trouble finding enough prey on land and shell fish was the only easy source of food to eat at around this time? Whatever the way it started, we can safely assume that at some point humans must have noticed these large-scale patterns in nature to know when and where to gather food from the oceans rather than run around during the day to find prey and hope everything will be okay. Of course, once these humans eventually migrated further north and enter the temperate zones of Europe, they had to devise ways of measuring time over a long period of time representing roughly a year by building circular stone monuments to help record the position of the Sun in the sky, as this helps humans to plan ahead and know when certain animals seen as a source of food would return. Otherwise, they can gather and store enough food as humans discover or identify the arrival of the distinct seasons and when to prepare for the colder winter months.

155,000 YEARS AGO

From those moments of increased abstract thinking came not just improved memory but also the emergence of a worldwide human phenomenon known as rock art — considered by scientists as the first signs of a cultural revolution. Not long after, religion and the development of a written language suddenly appeared as people began to acknowledge, record on rock surfaces, and later give special sounds and draw symbols to the things that were important to them for their survival as well as contemplate the purpose of life and death and the nature of the universe.

Rock art would also form the beginnings of recording human knowledge lasting many thousands of years.

Initially, the creative outpourings on rocks and cave walls showed the shapes of various animals hunted by early humans and showing spears being thrown through the air. Sometimes more dangerous animals may be recorded in a more frightening way all for the purposes of revealing to future generations the evil spirits residing in these creatures (and hence should be avoided or given greater respect). Some other images would reveal an acknowledgement of who the author was by leaving an outline of a human hand on the wall (i.e., a kind of primitive identification by way of a signature). This has the advantage of telling other tribes who created the pictures as a sign of ownership and possibly as a means of marking out a territory from one tribe and so hopefully prevent others from entering the area. The place is sacred and many people have passed away in the area. So respect the area and the people who lived there (or will soon return to live there again). While other forms of art showed a more creative streak by their human creators (we can only imagine what they are).

Rock art was the fastest way of teaching new generations of mostly young men which animals to hunt and how to hunt them and which predators to avoid so long as humans returned to the same area to these images.

Yet these smarter early humans weren't totally satisfied. The creative mind was looking for ways to make life easier. Well, why not? We are not here to bust our balls all the time just to survive. There are better things we could be doing.

So the first thing is what to do with all those rock arts? In particular, what happens if the artwork gets destroyed when humans come back?

The problem with rock art is that sometimes you do need to have this knowledge with you all the time, in the safe keeping of the elders in the nomadic group. And sometimes the caves you once inhabit might get taken over and the knowledge passed on to other competitive groups. Or occasionally the knowledge is lost forever by some destructive force of nature. There had to be a better way to preserve this knowledge within the group and yet still be able to go back to it at any time, and at the same time have it recorded onto some kind of a compact and portable surface for the knowledge to be easily carried and transferred to future generations within the group. Likewise the drawings had to be small enough and yet recognisable to allow a range of different patterns to be recorded on the same surface.

Even the weight of the material for recording the knowledge was something people had to consider very carefully. For example, the last thing people want to do is carry a whole bunch of stone tablets containing all the knowledge while they are being chased by a predator. It is just not a practical thing to be doing in a harsh and difficult environment and with many other animals trying to survive. Therefore, it had to be critical for people to discover the right medium for recording knowledge, which meant it had to be extremely lightweight and not just compact.

Then the drawings themselves had to be more refined and structured better so people can get the full picture in their minds of not only the specific objects at the heart of the knowledge, but also what to do, the method of dealing with those objects representing something in the real world in the most efficient and effective way, and so on.

Eventually as each successive generation passed on the drawings to the next with the occasional smart and highly creative individual learning to re-draw and simplify the drawings on cave walls into more basic and smaller symbols in order to save space and time, it wasn't long before humans decided to get really abstract in their drawings and started stringing together a group of these symbols to form what we might call a crude sentence. The sentence was more than an association of commonly accepted and relatively easy to recognise symbols (or names) linked to various observable things in the environment. As some clever people at the time would have asked, what should you do if you see something in the environment with that symbol to represent it? Should you run, or pick up a spear and chase it, or don't do anything and stand still? Again language had to evolve further to describe all the actions (called verbs) we had to perform to be successful. And when should these actions be applied and in what order? Clearly some structure and a decision on which direction to read symbols across a surface had to be made. In that way, the first thing you read will often be the first thing you should do before progressing to perform the next step.

Further evolution of the language would come when a symbolic system of measuring how much of something existed was incorporated. We call this the rudimentary beginnings of mathematics. Naturally this was an important addition to the language as it later helped to develop trade i.e., starting a business for selling things to other people in return for money).

Other members of the group (probably the females) would also learn about the new primitive language as some men in the relationships decided to share the knowledge (or perhaps women were sneaky to listen in and observe these symbols), adding their own symbols and sounds to help describe other things such as our emotions. Once emotions were incorporated into language and could be communicated with other humans, humans could for the first time develop some understanding of empathy for other humans (especially within a group and among family members) as a powerful means of developing deeper and more meaningful relationships within the group and so better understand how our actions truly affect people's emotions.

And when different groups of people in a certain locality developed their own unique symbols and sounds for the same observable things, actions, emotions and numbers, different languages developed. Soon there were groups of people speaking different sounds for essentially the same things. The advantage of doing this is that highly prized knowledge gathered by one group could be kept secretly within the group and used to the advantage of the group above all others when applied.

But as with any knowledge kept by a communicative tribe, time and enough thinking by other people will eventually discover the same knowledge. The question is, which language should be used by all humans to describe the same things? However, for early humans, there was enough competition in the environment. People have to survive. And if you are in a group with trusted members all doing their fair share and helping the group to survive, the knowledge you acquire may need to be kept within the group. So, to avoid the knowledge from being worked out by others and potentially making it harder for everyone to survive, sometimes a different language had to be spoken using different symbols. In that way, the group will have a distinct advantage over other groups, and a better chance of surviving in the environment.

This is the origin for the diverse range of languages humans have learned to speak and write over tens of thousands of years. But when trade came along, a need for a common language started to become important. Mathematics is perhaps the simplest and best understood language of all groups. But sometimes the art of negotiation and explaining the features and benefits of new products still needed words to be spoken and symbols to be written.

Never mind. One thing is certain. Verbal communications certainly became important for humans. Indeed there would be times when you need to be able to communicate with others even if they do not speak your specific language. This was the main issue for a group of entrepreneurial people who wanted to set up a form of trade in order to exchange, barter, buy or sell valuable goods and services considered of great benefit to various groups involved in the trade. So the first important standardisation that had to take place was in the numbering system for counting how many things there were. Once an accepted means of counting was found, the language barrier could begin to be broken down between seemingly different groups.

NOTE: Today, human language is favouring three types: Spanish, English and Chinese. French and Russian are also common mainly because there are large numbers of people speaking those languages. But in terms of the largest numbers of people, Spanish, English and Chinese are the ones to stand out the most. Spanish is considered the most widely-spoken partly from the shear numbers of people living in Spanish-speaking countries, but also because it is the easiest to learn and speak compared to say English or Chinese. English is the next popular language and is fast growing as becoming possibly the preferred international language, mainly because of its flexibility and ability to come up with many new words to describe just about anything (so long as other people agree to the new words and their meanings). Chinese remains a major language mainly for the shear numbers of people living in China. All other minor languages such as French, German and so on are kept for cultural and historical reasons and so maintain a sense of unique identity and of belonging to a specific group. As for other languages, a number of them are rapidly disappearing.

150,000 to 130,000 YEARS AGO

The end of another great ice age around 150,000 years ago (4) had encouraged yet another major migration of the more intelligent and communicative hominids from central and southern Africa to other parts of the world. The great ice age of this time was known as the Marine Isotope Stage 6 period (named in part because of analysing oxygen isotopes from deep-sea sediment samples). Basically, it was a specific type of ice age when not only did the polar caps and glaciers around the world expand, but deserts did too as the atmosphere effectively had its moisture sucked out of it by the ice. Combined with the colder conditions, food supplies dwindled over significant parts of central, eastern and southeastern Africa where, at the time, all known humans lived (as far as the fossil records would indicate). Before enough humans migrated, it’s estimated that the human population at this time could have dropped down to under 1,000 people.

Among the locations visited by these early and smarter humans included North America, according to the work of palaeontologist Richard Cerutti, from the San Diego natural history museum, after discovering a Mastadon tusk standing in a position that could not be natural but the result of some intelligent human(s) that had arrived in the California region of the continent. Carbon-dating of the site indicates the tusk is 130,000 years old. It is unclear whether the animal died by the hands of humans. A giant Dire Wolf skeleton was found nearby and it is known these predators did work together in a pack to hunt down Mastadons.

Although the Mastodon carcass had laid on the plains for months as it was picked at by scavengers, it seems the bleached bones were found by a group of early humans. The Archaeological dig found primitive stone tools, including anvils and hammerstones laying alongside the Mastodon bones. These tools were used to break open the bones by these mysterious humans to help reach the fresh nutritious bone marrow. Then, strangely, one of the Mastodon tusks had been purposefully left standing by these primitive humans for reasons no on can explain as yet. The tell-tale signs of human activity has been firmly established. As paleontologist Daniel Fisher could surmise from the investigation:

"We don't know how this animal died. We don't know whether humans were part of that death. All that we know is that humans came along some time after the death, and they very strategically set up a process involving the harvesting of marrow from the long bones and the recovery of dense fragments of bone that they could use as raw material for producing tools."

If humans did arrive to North America at around 130,000 years ago, it would make sense considering there had been a land bridge formed between Asia and North America. But even so, why would humans migrate during this very cold period in Earth's history? What's wrong with staying near the equator for some warmth and extra food supplies? Only one problem: the great food bowl of Africa was diminishing over time due to the drier conditions thanks to an increasing rain shadow formed by the growing Himalayan mountains, as well as the impact of early humans and other hominids on the great African environment. And, of course, there was the great ice age of around 150,000 years ago to create drier and colder air to travel further towards the equator. For those hominids who choose to move to the equator for warmth and the hope of more food, they would have to be contented with facing extra competition from other hominids congregating in the same equatorial regions. Either food supplies were diminishing and/or there was extra conflict between certain groups could have been common. Perhaps a perfect storm had been brewing at around this time to force some humans to migrate north. Not so much into the colder on land travels, but preferably along the eastern African coast for a more constant and warmer temperature. Then over time, these hominids travelled up the coast and headed towards the Middle East, and from there could have headed east or west.

Were there other migrations taking place around this time? It is not clear, for instance, whether there was a migration from Asia back to Europe and Africa. We know hominids did exist in south-east Asia before the start of this interglacial period. Maybe the Asian people found it too comfortable and safe living near the equator in relative isolation from the rest of the world. And with the extra food supply, Asian people could meditate and perform more elaborate religious rituals to help them understand the true meaning of life and the universe? Or maybe some hominids did migrate, but not to Europe or Africa. It is likely some Asian hominids travelled into northern Russia and later North America through the land bridge (or used boats to travel along the coast) created during the Ice Age between Russia and Alaska and eventually into South America.

At any rate, we do know a number of hominids did migrate to Europe from Africa.

One can understand how the new modern European settlers have much in common with their African counterparts thanks to their highly competitive nature in getting things of a survival nature. The likelihood of these new early Europeans engaging in warfare would be high compared to, say, Asians who were probably more peaceful and living in a more food abundant environment and hence the decision for these people to be more co-operative and take on a more creative approach to life might be stronger so long as some Asian people didn't get too obsessed with power and wanting to rule the people. There is something about high population levels and limited food supplies that tend to bring out the best (e.g., bigger brain, more communication, increased socialisation etc.) and worse (fighting to eliminate other hominids) in people. In the latter case, the violent streak within the people of Africa and Europe could have been common as if fighting was seen as the only immediate solution to reducing the competition from other humans and ensuring food and territory is controlled.

However, at around 150,000 years ago, the need to fight other hominids became less important in Europe once they got there or were already living in the area. Apart from the fewer hominids living in Europe, maybe the previous Ice Age was too cold for other hominids to make this remote continent their home, let alone find the energy to throw a spear at another hominid when one's butt is being frozen. However, as soon as the interglacial period returned, there was an opportunity for migrating hominids to move into Europe. Then the hominids could relax a little more and focus on the task of gathering new foods while living in caves. While other people may have discovered geographical gems in Europe (such as hot springs in places where Germany is now located) for staying warm and protected while gathering and/or growing food with relative ease and these people may have wanted to protect these sites at all costs. If so, conflict could be common.

Then the next Ice Age returned and some European hominids would rely significantly on animals for food and warmth, while some other hominids probably moved back into Africa or elsewhere for greater warmth.

The first early settlers of Europe at this time were known as the Neanderthals. These people were a tough brute — a truly great survivor for more than 100,000 years, and living through various ice ages on the continent. However, their time would eventually come to an end mainly because they continued to live either on their own or in very small groups and found it difficult to quickly learn new ideas or ways of surviving especially when the new breed of humans from Africa came into their territory. At first, and during the end of subsequent ice ages, the difference in intelligence and problem-solving was not significant. Any African hominids migrating to Europe in the interglacial periods quickly returned at the start of the next Ice Age. But with each cycle of Ice Age and no Ice Age, the African hominids were getting smarter. They were learning new techniques in hunting and socialising, and developing new weapons, together with a language to quickly organise the group and achieve tasks.

The Neanderthals, on the other hand, had little competition to worry about. Each group of Neanderthals usually kept to themselves and had their own territory. But all time was about to change, thanks to the arrival of the new African people who found a different way to adapt to the European conditions and seasons and make it their home. The Neanderthals method of survival was more to keep away from other "foreign" hominids, keep warm in the winter inside caves and wearing animal hides, and using sheer brute strength combined with an element of surprise and having enough strong males to throw large rocks at large Wolly Mammoths and other animals that were moving below a ravine. Otherwise, trees would have to provide some form of concealment before suddenly running a short distance to pierce the prey with their spears.

The new African immigrants were more organised and better adapters of the changing world (in fact, they could change the world to suit their particular needs by doing things like establishing territory, cutting down trees not just for firewood but also to build enough wooden houses, as well as protecting the boundaries to ensure they have first pick of the available resources available in their territory).

Not only that, but these highly competitive new humans emerging from Africa and heading into Europe knew a thing or two about how to protect their territories, including dealing with other hominids should they enter those territories without permission (i.e., the action will be perceived as a threat to the survival of the humans owning the territories in many situations). Furthermore, these sophisticated tool-wielding humans were very smart, understood the power of socialising, and had a well-established communicative language to boot. Add to this a collection of new weapons, such as spears to throw at a distance and move quickly, and a large brute such as the Neanderthals would have trouble chasing the new human invaders away from Europe.

A very intelligent and cunning new human breed had arrived into Europe.

Plus these new humans looked sufficiently different to the Neanderthals. Even though there are scientists who argue the Neanderthals looked fairly human-like, especially at a young age, the reality, the thicker brow ridge and flatter forehead made it clear to the new humans of a different species. We must remember that the new people from Africa had thinner brow ridges, a larger and more frontal expanded skull, a thinner and more delicate jaw, and a thinner and lighter body structure compared to the Neanderthals. Anyone that looked sufficiently different from these physical characteristics was likely to be perceived as a threat to the survival of the new humans, or simply not considered intelligent enough.

Some scientists would like to paint a positive picture of our humanity embracing at least some of these Neanderthals into society in some lovey dovey way. Certainly DNA analysis of modern humans has revealed some intermingling with the Neanderthals (most likely among young females). But Neanderthals were heading for extinction. Far from thriving side--by-side with the new people, the Neanderthals were struggling to co-exist, and not all humans were willing to share their territory, especially if they did not look the same or speak the same language.

These are the sorts of things we need to consider if we are to determine how these Neanderthals and modern humans survived in the same territory we call Europe. Would one hominid dominate the other? Or would there be a sharing and intermingling of the two groups? Modern analysis of mitochondrial DNA found in well-preserved fossilized remains of early humans and Neanderthals inside some caves are indicating some intermingling had taken place, mainly between male homo sapiens and female Neanderthals, but not the other way around. Due to the differences in facial features, especially among male Neanderthals, this kind of integration into human life was kept to a minimum as if other humans probably frowned upon their own kind having any sort of frisky sexual behaviour among different hominid species.

130,000 YEARS AGO

The Wolf Creek crater in Western Australia is created by a 50,000 ton meteorite travelling at 15 km/s.

100,000 to 90,000 YEARS AGO

Oldest known personal adornment pieces shows evidence of symbolic thinking at around this time. The pieces were excavated from archaeological sites at Skhul in Israel and Qued Djebbana in Algeria. These are shells known as Nassarius gibbosulus of 1 centimetre diameter with holes pierced into them by humans to allow a natural fibre string to pass through them to form a necklace or something similar. The discovery was made by Marian Vanhaeren at University College London and her colleagues while searching the world museum collections.

As co-author of the study, Francesco d'Errico of the National Center for Scientific Research in Talence, France, said:

"Our paper supports the scenario that modern humans in Africa developed behaviors that are considered modern quite early in time, so that in fact these people were probably not just biologically modern but also culturally and cognitively modern, at least to some degree."

Vanhaeren added:

"Symbolically mediated behaviour is one of the few unchallenged and universally accepted markers of modernity. A key characteristic of all symbols is that their meaning is assigned by arbitrary, socially constructed conventions and it permits the storage and display of information."

The finding is based on three shells analysed. Two of the shells from Skhul in Israel were 100,000 years old and the third shell excavated in the 1940s from Algeria was 90,000 years old.

Further details of the finding can be read in the 23 June issue of the research journal Science.

85,000 YEARS AGO