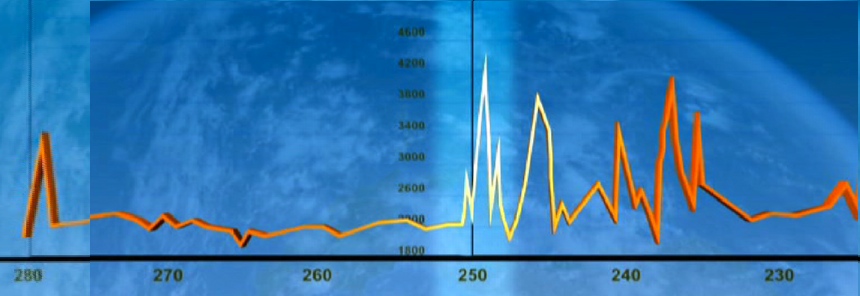

280 MILLION YEARS AGO

Widespread glaciation covers much of what we now call southern Africa, South America, Australia, and Antarctica (also known as Gondwana land) probably as a result of the high levels of oxygen in the atmosphere and the reduction in greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide due to high plant populations across the globe.

278 MILLION YEARS AGO

Methane levels in the atmosphere increased by around 278 million years ago, raising world temperatures by at least 5°C. This may have been enough to see the earlier widespread glaciation retreat in favour of more balmy conditions for supporting life.

Image © 2010 Catalyst televised on ABC, 16 September 2010.

260 MILLION YEARS AGO

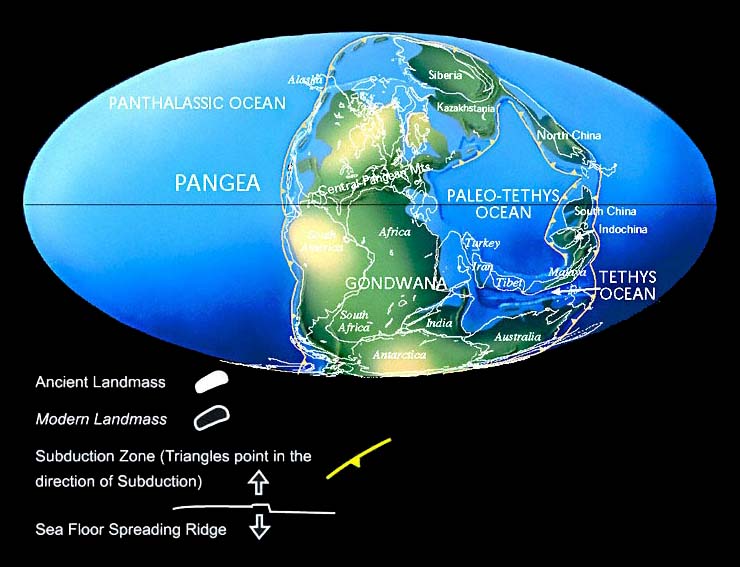

Fossils of particular ancient plants and animals have been found throughout all the southern continents of today, suggesting that Africa, South America, Australia and Antarctica were once joined together in a single supercontinent in Earth's southern hemisphere known as Pangea. Among the plants found include Glossopteris, an ancient tree forming an important part of the huge forests covering Australia and other parts of the supercontinent.

Insects rapidly diversified.

NOTE: The great land mass being located in what we call the southern hemisphere is an assumption for the Earth can, and has, flipped on its axis at various times throughout its long geological history (often as a result of impacts with the Earth by large meteorites or comets, or the sudden imbalance in the Earth's weight when a massive volcano erupts).

255 MILLION YEARS AGO

The weather conditions throughout the world began to change. Things were warming up again.

252.6 MILLION YEARS AGO

The mother-of-all extinctions in the history of life on Earth took place at around 252.6 million years ago give or take approximately 200,000 years thanks to an improved method for dating minerals in ancient rocks by Ian Metcalfe, deputy director of the University of New England Asia Centre in Armidale, NSW (the research work has been published in Science, 17 September 2004, under the title Age and Timing of the Permian Mass Extinctions: U/Pb Dating of Closed-System Zircons). So massive was this extinction that nearly 96 percent of all marine species, at least half the main group of animals, many plant species, and up to 85 percent of all genera disappeared forever. This was a really big event to hit the planet. The trilobites, which successfully survived for over 300 million years as a voracious ocean-floor scavenger, also became extinct.

What caused the massive extinction — an event known to the scientists as the "Great Dying"?

Prior to 23 February 2001, a few scientists came up with several imaginative explanations.

At first, some scientists thought the extinction had something to do with a severe change in climate. Certainly scientists found evidence for massive climate change at this time with increases in the amount of carbon dioxide and methane. Whatever caused this massive release in the greenhouse gases, it seems conditions were warming-up forcing shallow seas and swamps on land to dry up, and possibly helping to create the vast desert-like expanses in the interior of the great supercontinent. Despite noting a change in climate, the scientists still had trouble explaining exactly what had caused the climate to change in the first place. Was there a high concentration of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere combined with a sudden energy burst from the early, but growing Sun?

Other scientists suggested the Earth had probably passed through one of the spiral arms of the Milky Way galaxy where an ageing supergiant star lying near the vicinity of our Sun suddenly exploded, showing the Earth for a brief moment with deadly cosmic and gamma radiation.

Then in February 2001, Luanne Becker of the University of Washington in Seattle and her colleagues announced the discovery of what appears to be a very large ancient crater not far from the east coast of South Africa (1). Becker claims (as published in Science under the title Impact Event at the Permian-Triassic Boundary: Evidence from Extraterrestrial Noble Gases in Fullerenes) that her team analysed rocks in the area and noticed the presence of a reasonable amount of helium and argon of an unusual isotope not found on Earth but is readily available in meteorites. To make the discovery even more interesting, geological tests conducted on the rocks to help estimate the age of the crater all suggest the event had occurred at the end of the Permian period give or take a few million years. The results reached by this study was published in The New York Times where the public was treated to the latest interesting news on 23 February 2001 in the article Meteor crash led to extinctions in era before dinosaurs.

Despite this work, some controversy still emerged later in 2001 from other scientists claiming they were unable to reproduce the results. Among the scientists questioning Becker's claims included Yukio Isozaki of the University of Tokyo using a sample of rock from a site in China that was located in the same area during the Permian time as the place we call South Africa. However, Becker and her team remain firmly convinced of their results. Indeed, they repeated their analyses, this time using the Chinese sample and confirmed the presence of the unusual helium isotope. In another independent test in September 2001, Kunio Kaiho of Tohoku University in Japan obtained sediment grains in China corresponding from the Permian-Triassic boundary period. Kaiho succeeded in finding evidence of compression by some kind of impact, thereby supporting Becker's theory of a possible asteroid impact.

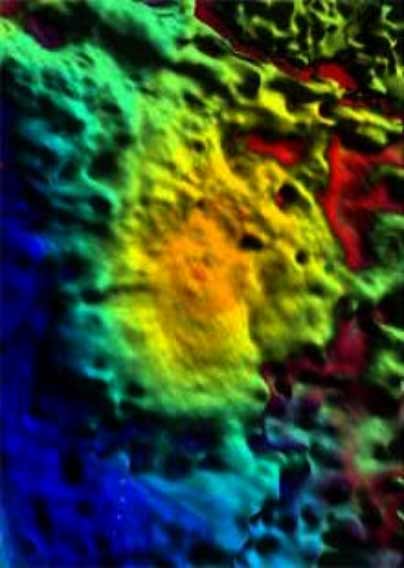

Not long after this discovery, scientists noticed yet another large crater buried off the northwest corner of Australia. In one of the few places in the world where rocks have not yet been recycled by tectonic plate movements, the Australian continent reveals a crater nearly 193 kilometres in size. And the age of the rocks in this region have been dated to around this time.

The Bedout crater (pronounced Beh-doo), or Bedout High as it is now called, is impressive to say the least. It makes the Arizona crater of more recent times (about 50,000 years ago) look like the impact of a speck of sugar in a tea cup compared to the massive sugar cube "storm in a tea cup" type of collision from this ancient asteroid. Whether the Bedout crater is part of the same massive crater near South Africa when Australia was closer to the African continent is hard to tell at the moment. Clearly both sites are large and appeared to have occurred at around the end of the Permian period.

Evidence to support what appears to be an impact site outside the Australian continent was found after studying the crystalline structures making up the melted rock layers drilled out by oil companies several decades ago on a ridge at the Bedout site. Apparently the oil companies had kept core samples from the area until it was analysed more closely by the team of scientists led by researcher Luann Becker of the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA (2). Now Becker is confident the crystalline structures show evidence of a "shocked" pattern in the quartz considered characteristic of an impact by a large rock in the area (either a meteor or something much larger such as an asteroid).

Understandably, other scientists remained unconvinced thinking another explanation exists. For example, another classic tell-tale sign of an extra-terrestrial impact is the presence of high concentrations of the rare element known as iridium. Only problem is that iridium was not showing up in the scientific instruments to convince everyone we definite have evidence of an asteroid impact. Today, scientists are still furiously debating whether the Bedout crater is, in fact, a crater. As Peter D. Ward, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, USA, said:

"It's not yet persuasive that it's even a crater." (3)

In that case, the safest bet at the present time is to assume the Earth experienced massive volcanic eruptions not triggered by any other event, and especially not an extra-terrestrial one such as an asteroid. As Professor Metcalfe said:

"We think the volcanic eruptions were the main cause [of the extinction], but there may have been several things coming together at the same time to produce the devastation of life."

Given the quantities of greenhouse gases prevalent in the Permian atmosphere, Professor Metcalfe has to call this super volcanism. Perhaps a bit like the supervolcano lurking beneath Yellowstone National Park today but even bigger.

Or could it be both?

If an asteroid makes a direct hit in a shallow sea and disappears into the magma, any remnants of the crater and specific elements, such as iridium, to prove the asteroid's presence could have been hidden by the subsequent and intense volcanism. Well, something had to have started the volcanism, right? Otherwise we do have the mother-of-all volcanism and the bigger supervolcano in Earth's history.

Despite the continuing controversy, the one thing everyone does seem to agree on is how the Earth experienced what was probably the most severe greenhouse environment ever known, with temperatures rising more than 10°C (and probably closer to 20°C) in less than a decade. For the next 5 million years, temperatures reached somewhere between 50 and 60°C on land during the day (perhaps warmer), and 40°C at the sea surface according to researchers at the University of Leeds and China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), in collaboration with the University of Erlangen-Nurnburg (Germany). If there was any respite for the animals on land, they had the forests and ferns to provide some shade to keep the temperatures down. But there is one problem. If the trees suddenly lost acceess to freshwater and the higher temperatures caused a drying up of the plants, massive bushfires could have swept the landmass.

Yadong Sun, who led the team of researchers and the lead author, used a technique to measure the levels of isotopes for oxygen in the fossilized skeletons and teeth of animals dated to the end of the Permian period and into the early Triassic period. Any variation in these oxygen isotopes is known to be temperature-controlled. So when these isotopes were compared to the bones of animals today, scientists gained a remarkably good insight into the general global temperatures in the past, even right back to the Permian times.

As a result, the study showed some kind of massive decimation of the plant species had definitely occurred on a worldwide basis at the end of the Permian period. This was followed by a massive increase in carbon dioxide levels as if massive volcanism was taking place. However, the dramatic rise in temperature suggests another more potent greenhouse gas may have contributed to the massive increase in global temperatures through a positive feedback system that helped to further release more carbon dioxide from plants as they dried up and got burned in ferocious bushfires and later more of this other greenhouse gas in a kind of runaway greenhouse effect. That other greenhouse gas is likely to be methane. Something had caused the methane hydrocarbon molecule locked away inside the hydrate ice structure deep in the ocean to be released in great bursts straight into the atmosphere. Since it is unlikely animals in the Permian period were starting an industrial revolution or creating fire (or even producing enough flatulence), this leaves us with massive volcanoes, a massive asteroid impact (or several impacts), or a combination of the two as the likely culprit for the great mass extinction.

Further details of the Yadong's study can be found in the journal Science, 19 October 2012 under the title Lethally Hot Temperatures during the Early Triassic Greenhouse).

Or was it just one asteroid responsible for the massive change in global temperatures? If it was, the general consensus is that it had to have been no less than 11 kilometres in width (others claim perhaps even 16 kilometres wide, or roughly the size of Mount Everest) that crashed to Earth resulting in massive volcanoes springing up in what is now India. The shock waves resulting from this massive impact travelled to near the opposite side of the Earth where the world's biggest volcanoes and earthquakes suddenly erupted over Siberia. For nearly a million years after the impact, lava poured from these volcanoes (estimated to be in the thousands) in such great quantities that if the Earth was absolutely smooth, the lava would have covered the entire planet up to 10 metres thick. But since the Earth is not absolutely smooth, it is likely that at least a quarter (if not more than half) of the Earth's solid surface had suddenly become covered with red hot molten rock. So it would seem plausible that any life that tried to rely heavily on its ability to crawl at the bottom of the ocean looking for food had soon perished.

Plant life certainly took a serious battering at this time with scientists such as Yadong Sun claiming the tropics rained almost continuously but very little plant life existed which may explain the lack of hard evidence to show coal deposits had formed during the early Triassic period. As Yadong Sun said:

"Global warming has long been linked to the end-Permian mass extinction, but this study is the first to show extreme temperatures kept life from re-starting in Equatorial latitudes for millions of years."

In other words, as many of the rainforest trees dried up and burned, the dust allowed the humidity in the tropics to condense and fall as rain onto a predominantly dry and barren landscape.

The oceans were also depleted or seriously reduced in the numbers of fish and marine reptiles except shellfish. As for land-based animals, they couldn't survive in equatorial and most temperate regions of the planet (aptly named the dead zone by Yadong just to ram home the idea) unless they took refuge in caves, or underneath any patchy remnants of plants at certain altitudes. In fact, of all the places on the planet, the polar regions were the best places to survive this catastrophic event.

Unless land-based animals could withstand reasonably high temperatures or at least find places to regularly cool down, it seems nearly all the primitive amphibians and reptiles quickly perished. Another creature not to fair well under the sudden temperature rises were coral and sea lilies.

The link between mass extinctions, volcanoes, methane emissions, global warming and asteroid impacts in any or all such combinations and the likelihood this might be a common occurrence is being supported by some scientists including researcher Ms Becker when she said:

"We think that mass extinctions may be defined by catastrophes like impact and volcanism occurring synchronously in time." (4)

Further studies are continuing to prove or disprove Becker's interesting claim. But one thing is certain: this extraordinary event is the closest life on Earth has ever got to being totally snuffed out by a piece of rock drifting through space (assuming an asteroid had started this event).

UPDATE

4 June 2006

A scientific team led by Dr Ralph von Frese and Laramie Potts of Ohio State University have found yet another crater (but no direct evidence of its age). This one is big. So big that scientists say they have found the Earth's biggest known crater. At 300 miles (482 km) wide, it is twice the size of the Yucatan peninsula's Chicxulub crater that killed off the dinosaurs nearly 64 million years ago.

The crater is hidden beneath East Antarctic ice in the Wilkes Land region, directly south of the continent of Australia. It was noticed only after NASA satellites measured the gravitational field over the surface of the Earth where an anomaly was found in this region. The anomaly consists of a circular ridge and a massive central plug of material suddenly risen up into the crust. Scientists believe this is a classic tell-tale sign of a massive impact crater resulting in the denser mantle bouncing up into the crust above.

An impact of this sort suggests an asteroid of 30 miles (48 km) wide could have created it. Life would definitely not have been happy at this time. As von Frese said:

"All the environmental changes that would have resulted from the impact would have created a highly caustic environment that was really hard to endure."

Whatever the cause for the global warming at the end of the Permian period, that fact that the planet can reach phenomenal temperatures through an emission of methane from under the oceans has important implications for humankind today. As the planet heads towards yet another similar high temperature environment, we must all be mindful of the consequences to life on Earth. True, some R-wing people might think this is great for reducing the numbers of ageing people who will die from heat-related stress, leaving behind the young to support the economy, while the rich and powerful R-wing types spend up big on electricity to power their air conditioners with the profit earned from the young people. But the rest of life beyond our human-centric society is unlikely to benefit from this. In which case, should the ecosystem collapse as a result, human civilisation will certainly come to an end too. Don't like the idea? In that case, there will need to be significant changes to society today and what we do in our economy if we are ever to survive the inevitable global warming of today. Let us hope we are smart enough and our technology great enough if time is not on our side to get us out of this latest situation.

For a final word on the subject, Professor Paul Wignall from the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds said in the press release of Yadong et al's study:

"Nobody has ever dared say that past climates attained these levels of heat. Hopefully future global warming won't get anywhere near temperatures of 250 million years ago, but if it does we have shown that it may take millions of years to recover."